Before software.

Before prompts.

Before output.

There is seeing.

As a new academic year begins, I’ve found myself returning to a quieter question — not what students should make, but how they learn to notice. In a creative landscape increasingly defined by speed, automation, and instant visual results, the ability to slow down and observe has quietly become a radical skill.

Seeing, after all, is not passive.

It is trained.

It is practised.

It is disciplined.

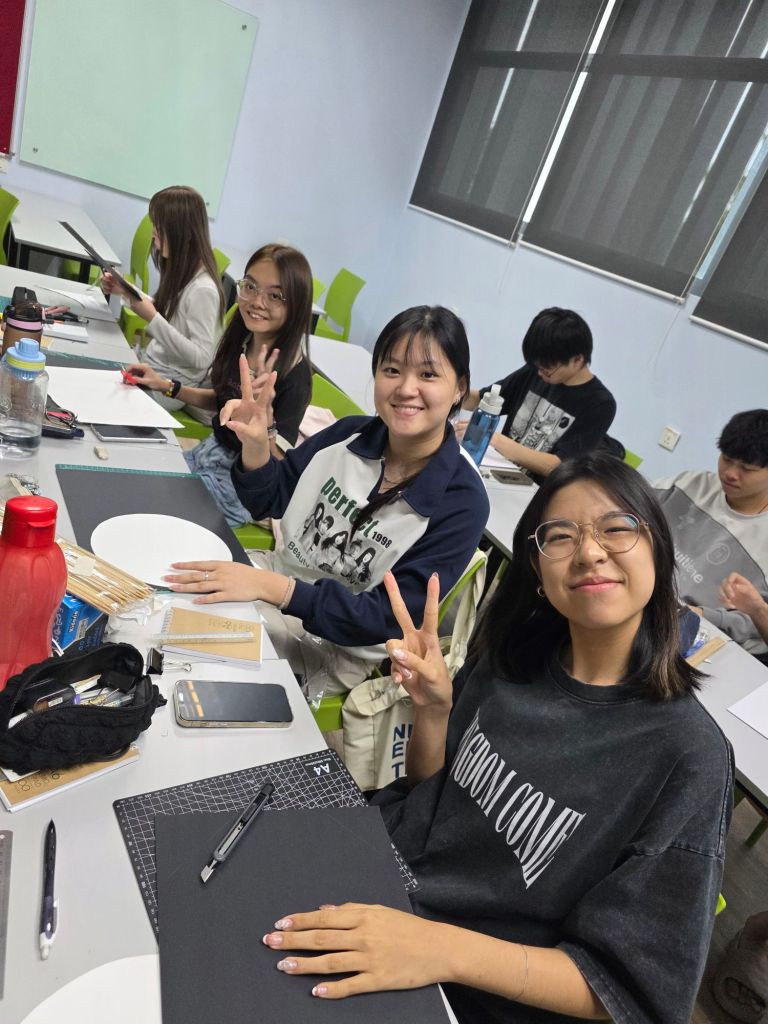

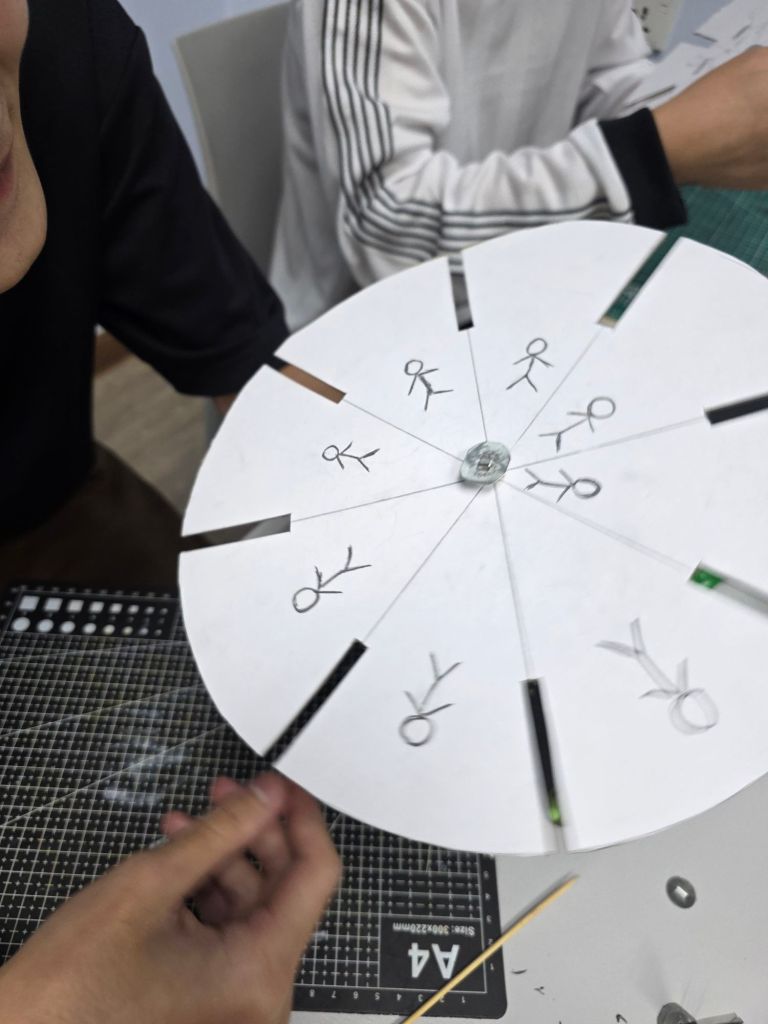

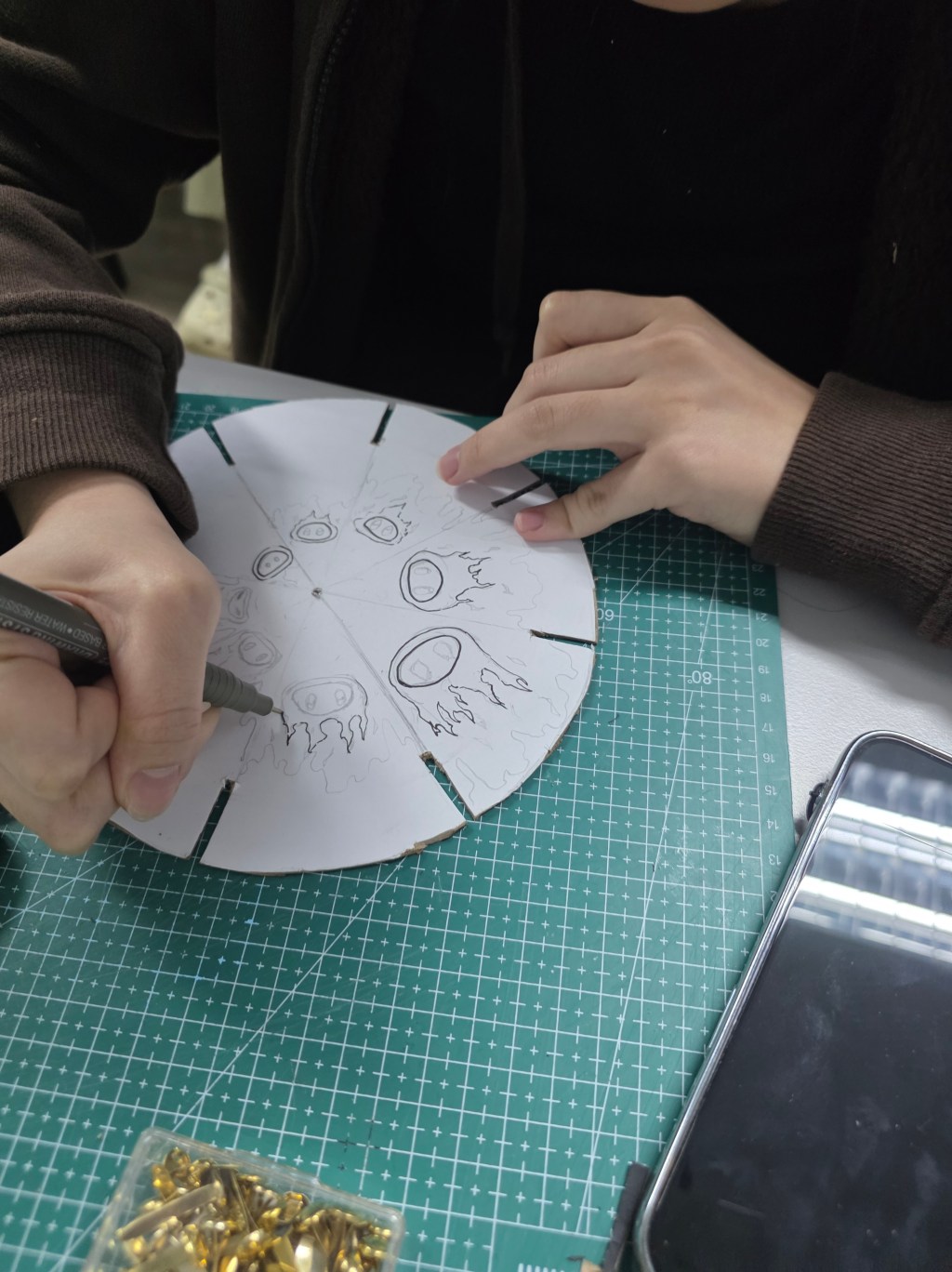

This belief surfaced clearly during the opening weeks of History of Animation, where we deliberately stepped away from screens and returned to fundamentals. Instead of beginning with digital tools or animation software, students were asked to build their own phenakistoscope — one of the earliest devices to demonstrate the principle of persistence of vision.

Paper.

Cutting tools.

Markers.

Movement.

Nothing more.

In constructing these simple optical toys, students weren’t just recreating history. They were learning to observe motion frame by frame — to understand how still images gain life through sequence, timing, and rhythm. There was no undo button. No playback scrubber. Every decision had weight.

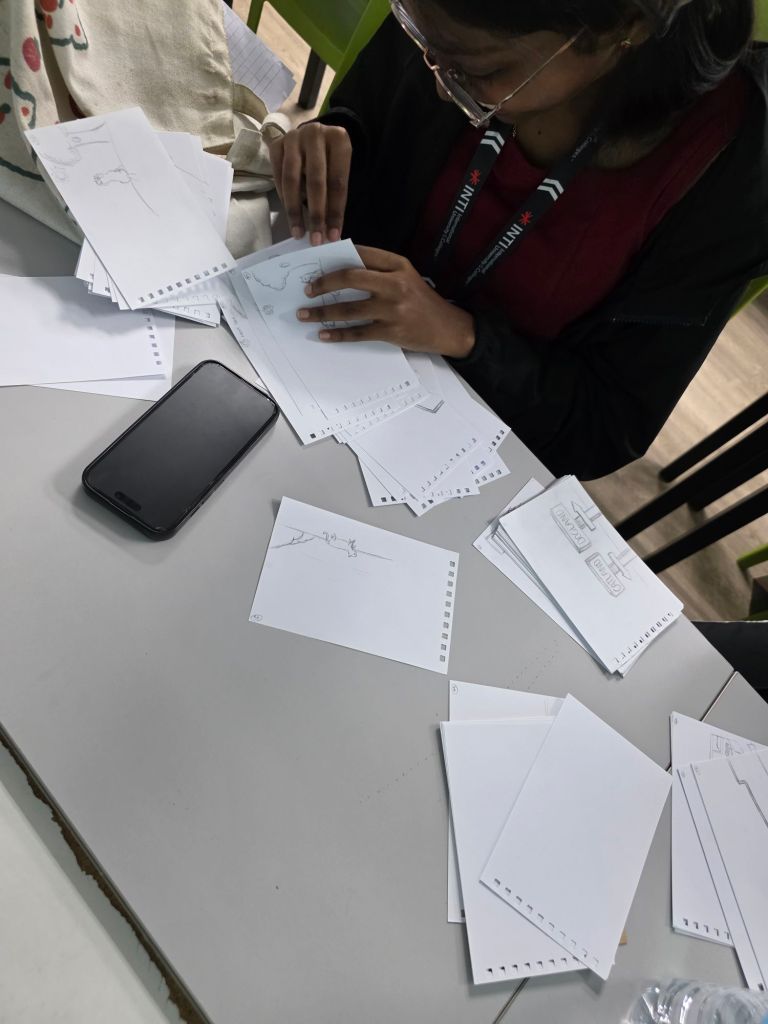

The lesson culminated in a flipbook challenge, where students were tasked to apply what they had learned independently over the following week. The brief was intentionally modest: create a short frame-by-frame animation, then return to share the process, the outcome, and a reflection on what worked — and what didn’t.

What mattered wasn’t polish. It was awareness.

I think this activity was really fun! The hardest part for me while making the flip book was making sure that every object stayed in the same place and kept the same shape in each frame. — Xuan Xuan

Through this exercise, students experienced animation not as spectacle, but as construction. They began to grasp that motion is built incrementally, that meaning emerges through repetition, and that attention to small changes is what makes movement believable. In other words, they learned to see before they learned to produce.

This early encounter with persistence of vision does more than introduce animation history. It lays a conceptual foundation for what comes next — 2D animation, 3D animation, motion graphics. Long before timelines and keyframes enter the picture, students develop a felt understanding of how motion works, and why every frame matters.

And this is where my personal teaching aim becomes clear.

The inclusion of advanced technology — from industry software to AI-assisted tools — is not something I resist. It is something I plan for. But alongside these developments, my intention has been to ensure that students experience learning in a humanistic way — one that prioritises perception, judgement, empathy, and embodied understanding.

Technology may accelerate execution, but it cannot replace experience. Tools may generate options, but they cannot teach discernment.

By grounding students early in analogue, sensory-based exploration, they are better prepared to engage with advanced tools thoughtfully rather than dependently. They learn not just how to use technology, but when and why it should be used.

Before tools shape outcomes, perception shapes intention. Before automation accelerates production, observation grounds judgement.

Before AI assists creation, attention gives it meaning.

When students learn to see — truly see — they don’t just become better animators. They become more thoughtful designers. They understand that making is not a race toward results, but a process of noticing, adjusting, and responding.

This is not nostalgia for analogue methods, nor resistance to technology. It is a commitment to balance. In an age of increasingly powerful tools, the most important thing we can offer students is not speed, but clarity.

January 2026, now, feels like the right moment to pause here.

- To re-centre on perception.

- To value attention as a creative discipline.

- To remember that before we ask students to produce, we must first teach them to observe.

The applications will come. The tools will follow. The outputs will arrive in time.

But first, we learn to see again.

Leave a comment